In this post, Patricia Banks, author of the just-published Race, Ethnicity, and Consumption, reflects on how consumer-focused companies’ social media reacted to this spring and summer’s racial justice protests, as well as the subsequent activist response, neatly weaving it all through the important concept of ‘racialized political consumerism.’

– Michaela DeSoucey (section chair)

Consume This! Consumer Activism and Corporate Diversity

By Patricia A. Banks, Mount Holyoke College

In the days after the deaths of George Floyd and other African Americans, protests broke out across the United States. While police brutality was a core focus of the unrest, an emergent strand of activism was directed at businesses. Corporate America, some critics charged, was failing to diversify its ranks. Over the course of the summer, consumer activists targeted companies to make progress around workforce diversity. As I discuss in my new book, Race, Ethnicity and Consumption: A Sociological View, the use of consumer activism to pressure companies to diversify is not unprecedented.

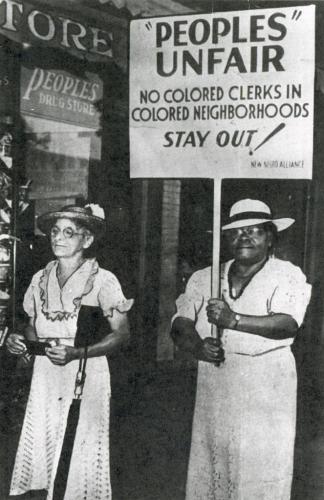

Among the topics explored in the book’s chapter on social activism is racialized political consumerism—consumer activities aimed at “influenc[ing] how resources are allocated toward a specific racial group.” In the United States, there is a long history of racialized political consumerism directed at diversifying the workforce. For example, activists involved in “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaigns in the 1920s to 1940s picketed in front of stores where African Americans could shop but were banned from employment. Similarly, in the 1960s and 1970s, civil rights activists boycotted businesses that refused to hire African Americans into management positions. Consumer activism that emerged in the summer of 2020 continues in this tradition.

In the wake of these most recent protests, a flurry of posts disavowing racism swept across corporate social media channels. Brands in the beauty industry, such as Revlon, L’Oréal, Neutrogena, and Shea Moisture, were especially active in making pro-diversity statements. For example, a May 31st Instagram post by global beauty corporation Estée Lauder included an image of a black box overlaid with the phrase “WE STAND WITH THE BLACK COMMUNITY” in white writing.

That same day, another major beauty company Coty, Inc. published an Instagram post stating that the business was “in support of Black Americans and people all over the world fighting for freedom, justice and equal opportunity.” Two days prior, cosmetics company Lush posted a colorful portrait of Floyd with accompanying text proclaiming that “Black Lives Matter” and “Staying Silent is not an option.” While these posts were intended to communicate that businesses were on the side of equity, they were dismissed by some consumers as mere window dressing. The Pull Up for Change movement, which emerged in response to these pro-equity posts, was aimed at pressuring companies to become more publicly accountable around their employee diversity, particularly that of black workers at the management level. This online movement was initiated by Sharon Chuter the founder of the Uoma Beauty brand.

On June 3rd, a series of posts on the Instagram account @pullupforchange called on companies that had made racial justice statements to post information about their employment of blacks in professional and managerial positions within the subsequent 72 hours. “You cannot say Black Lives Matter publicly when you don’t show us Black Lives Matter within your own homes and within your organizations. . . ,” Chuter remarked in a video accompanying one post. To pressure companies to publicize diversity figures, posts by the Pull Up for Change organization encouraged consumers to boycott companies.

For example, one post beginning “Dear Allies” asks that “For the next 72hrs DO NOT purchase from any brand and demand they release these figures.” Soon, social media users were leaving comments underneath corporate racial justice postings requesting that they publicize this information. Some comments just included the movement’s hashtag “pulluporshutup” while others included more extensive statements. For example, a commenter responding to an Estée Lauder post asked the company to “Please share the number of your black employees at corporate level, and the number of black people in LEADERSHIP ROLES! If it isn’t good enough please share these statistics with a sufficient actionable plan, including dates and figures about when and how you’ll improve, because I think your silence already shows you need to improve. Fab, thanks!”

Similarly, underneath a Revlon racial justice post a commenter wrote that “If your company doesn’t share @pullupforchange then I can no longer support you. I love your products but our lives need to matter.”

Within days, businesses started to respond to the appeals. In some cases posts not only included data about the diversity of employees, but also recognition that more work needed to be done in this area. For example, in an Instagram post L’Oréal USA reported that “Among our corporate (HQ) population . . . 7% identify as black and “Among our executive leadership team . . . 8% identify as black.” The post concluded, “We can, we must and we will do better. Transparency in conversations like this one are an important step. #pullupforchange #pulluporshutup.” Similarly, a post reporting that 2.9% of employees at the director level and above at Coty are black noted that the company “can do better.” The post ended by thanking “@pullupforchange for challenging us all.”

A post by Revlon showing an image of the Revlon logo above the pullupforchange hashtag noted that 5% of employees in the director and above level are black and acknowledged “that we are not where we need to be on diversity and representation at our company.” While it appears that company responses to movement demands were at their height during the peak of the summer protests, some companies addressed the Pull Up for Change challenge into the fall. For example, in an Instagram post in September, Lush reported “learnings” from a “90-Day Action Plan” launched a few months prior to address diversity, equity, and inclusion at the company. The post included a series of images with pie charts about employee diversity. “@pullupforchange” was written across the top of each image.

The concept of racialized political consumerism is key to understanding consumption in the past and present. This concept, as well as many others, are explored in Race, Ethnicity and Consumption which looks at the central concerns of consumer culture through the lens of race and ethnicity. In addition to social activism, other chapters examine identity, crossing cultures, marketing and advertising, neighborhoods, and discrimination. These chapters can offer insight on a wide-range of recent events, such as Johnson & Johnson pledging to stop selling skin-whitening products, the Uncle Ben’s brand changing its name to Ben’s Original, and the introduction of legislation to “explicitly outlaw” customer discrimination at banks. These issues illustrate the central argument made in Race, Ethnicity, and Consumption—that understanding racial inequality requires paying close attention to consumption.

About the Author

Patricia A. Banks is Co Editor-in-Chief of Poetics and Professor of Sociology at Mount Holyoke College. She is the author of the books Race, Ethnicity and Consumption: A Sociological View, Diversity and Philanthropy at African American Museums, and Represent: Art and Identity Among the Black Upper-Middle Class. In her research on corporate cultural patronage, Banks extends her investigation of race and cultural capital to organizations.

- Website: http://www.patriciaannbanks.com

- Email: pbanks@mtholyoke.edu

- Twitter: @PatriciaABanks

List of Images

- Figure 1: Mary McLeod Bethune pickets People’s Drug: 1940 ca / Washington Area Spark

- Figure 2: Race, Ethnicity, and Consumption A Sociological View / Routledge

Figure 3: Pull Up for Change post calling on consumers not to purchase from brands not posting diversity figures / Screenshot by author - Figure 4: Response to Pull Up for Change post by cosmetics brand Lush / Screenshot by author

Leave a comment